The School That Forest Falls Would Not Let Go Of

Shared by Tom McIntosh for 38 Bulletin

COMMUNITY STORIES

38bulletin.com

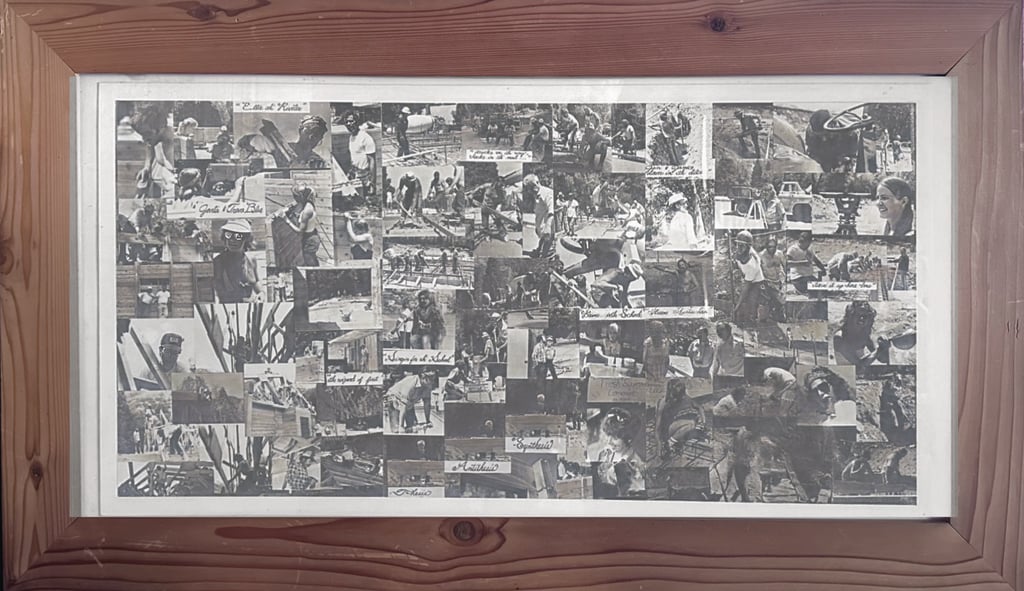

Photograph of a framed collection of pictures taken during the volunteer construction of the Fallsvale New School Facility Project- Hanging at Gilmore Real Estate Office

When the opportunity came about to sit down with Tom McIntosh and talk through his experiences during the years when Forest Falls faced the loss of its school, his name surfaced repeatedly as the person who would know the details. Not simply because he remembers them, but because he was so deeply involved, hands on, in bringing the school into existence. What follows is a story shaped from that interview, about a moment when this community chose action over acceptance.

Tom McIntosh arrived in Forest Falls in 1970 with his two young sons, in a community where the school was operating normally and quietly met the expectations any parent would rely on when choosing a place to live.

Then that all changed...

It wasn’t something he ever imagined would change. Small communities have schools the way they have post offices and firehouses. They are simply part of the place. By the time his boys were in kindergarten and second grade, the Fallsvale School was already stretched thin, squeezing two classrooms into a one room stone building that had outgrown itself.

That pressure is what drew attention to the building in the first place. The school district sent engineers up the mountain to look at expansion.

They didn’t come back with ideas.

They came back with warnings.

The issue wasn’t neglect or decay. The problem was structural and legal. The old stone and masonry schoolhouse had never been built to meet California’s Field Act earthquake safety requirements. In a major quake, engineers believed the unreinforced structure could fail catastrophically. Children should not have been inside it at all.

For a time, the district allowed classes to continue while alternatives were studied. Three more school years passed. Then attorneys stepped in. Once the district formally acknowledged the risk, continuing to hold classes there exposed board members to personal liability.

The district’s answer was straightforward.

Bus the children down the hill.

For Forest Falls, that answer landed as a hard no. Parents were clear. Their children would not spend hours each day on mountain roads as a long term solution. Not temporarily. Not permanently.

So the community did something unusual.

They decided to build their own school.

Tom did not frame it as dramatic. He stepped forward because someone had to. He took responsibility for organizing volunteer labor and joined a small group that carried the project forward from concept to reality.

The turning point came at a school board meeting in the late 1970s. Tom stood before the trustees on behalf of Forest Falls and said the community was willing to build a new school themselves.

The trustees listened. They respected the resolve, and they laid out the reality. This would be a public school, subject to the Office of the State Architect. Plans would require approval. Codes would have to be met or exceeded. Performance, completion, and material bonds would be mandatory.

Forest Falls did not back away.

Bob Tobias, a licensed general contractor who lived in the lower canyon, agreed to serve as general contractor. The school district committed funds it had set aside for years, roughly $280,000, enough to cover materials. Labor would be donated.

That part was assumed.

People showed up. First neighbors. Then people who heard about the project and drove up to help. Some stayed a day. Some stayed a week. By the end, many volunteers did not even live in the canyon.

What nearly stopped everything was paperwork.

No insurer wanted to write performance and completion bonds for a volunteer-built project. The risk did not fit a standard box. Media coverage helped, but it did not solve the problem. Then an insurance agent stepped forward and agreed to write the bonds, if the community could provide collateral.

Ten homeowners agreed.

Each posted a $10,000 bond, secured against their homes.

There was no ceremony around that decision. No speeches. Just signatures and trust. Ten families put their personal security on the line so a school could exist on the mountain.

Years later, that same insurance agent told them something that stayed with Tom. Even if the project had failed, he would never have foreclosed on those homes. He believed in what they were doing that much.

With the bonds in place, the work moved forward.

Union operating engineers donated heavy equipment labor as apprentice training. A civil engineer volunteered time to oversee compaction testing and certification. Every trench, every refill, every load was inspected and documented. This was not casual volunteerism. It was disciplined and accountable.

Fatigue still set in. People ran out of days off. Energy thinned. Tom and another core volunteer, Paul Forges, were there nearly every day and night to keep the project moving.

Then help came from an unexpected place.

The California Conservation Corps called and offered a crew of 25 young people. They did not bring trades. They brought labor. Forest Falls housed them, fed them, supervised them, and taught them what to do. Girls stayed in local homes. Boys slept upstairs in the firehouse. They worked four or five days a week.

Tom believed that may have been the difference between a stalled project and a finished school.

By January 1982, Fallsvale School opened its doors.

During construction, the children never left the canyon. Classes were held at Forest Home and at the Community Church. The disruption was real, but the connection remained intact.

Details mattered. In the bathrooms, tile became lizards, snakes, and mountain shapes. Small touches, but intentional. The building was not just safe. It was welcoming.

Tom described Forest Falls as a bedroom community, a place where people sleep but do not always fully live. The school pushed against that. Without it, the canyon would have lost more than a building. It would have lost part of its center.

Even after his own children grew up, Tom stayed engaged with the life of the community. When the school later faced closure again, the concern was no longer personal, but it was no less real. A school on the mountain meant families could remain rooted. It meant Forest Falls could continue to be more than a place people passed through.

Tom never talked about leadership as heroism. He called it persuasion. Selling an idea. Selling commitment. Selling follow through.

But the real fuel was simpler.

He could not imagine Forest Falls without a school and accept it.

So, he didn’t.

Connect

Stay informed with local community announcements

Engage!

Share!

© 2024. All rights reserved.

For updates about what's going on @ 38 Bulletin... Subscribe!